The Imperial Roots of Architectural Education

The Western origins of architectural pedagogy

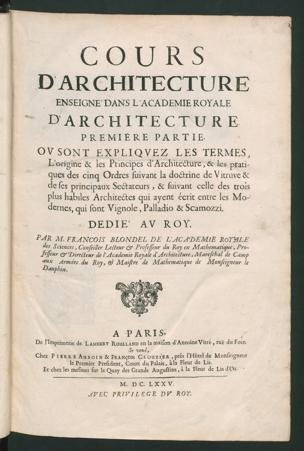

The method of teaching architecture in universities finds its roots in the Western society of the 18th century. Although the first official school of architecture, the Royal Academy of Architecture of Paris was established at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1671, it wasn’t until the late 18th century that the discipline began to be taught in universities throughout Europe. More significantly, it wasn’t until the 20th century that architectural education reached so-called "developing" countries at an academic level.

With the institutionalization of architectural education came the development of a structured "theory of architecture," heavily influenced by prominent Enlightenment figures like Charles-Nicolas Ledoux, Marc-Antoine Laugier, and Quatremère de Quincy. These thinkers sought to understand and explain the origins of architecture, and to define its "universal" principles, forming a theoretical framework that would profoundly influence subsequent generations, particularly modernists, who embraced these ideas as the core of their architectural philosophy.

However, contemporary scholars have highlighted the colonialist and imperialist roots of these founding theories. They advocate for a shift in how architectural history and education are approached, calling for a decolonial and anti-imperialist perspective. This involves actively challenging and rejecting the oppressive structures embedded within traditional pedagogies, promoting a more inclusive and critical framework for architectural education.

Taxonomy and racial theories

Although architecture is practiced universally, its teaching at the academic level originated in the West in the 18th century. When architectural pedagogy was introduced to so-called “developing” countries in the 20th century, it brought with it Western norms and references. The curriculum and methodologies were often based on European models, leaving little space for traditional and local architectural practices. Globally, higher architectural education became deeply imprinted by Western principles and styles, perpetuating the colonialist ideals rooted in Enlightenment thinking.

Historian Irene Cheng emphasizes how racial theories developed during the Enlightenment continue to influence architectural ideas today. The development of architectural theory and its formal academic teaching coincided with the rise of colonial enterprises, intertwining the two.

Enlightenment thinkers such as Pierre Camper, Charles White, and Georges-Louis Leclerc were among the first to produce taxonomies. These classification systems were used to justify colonial expansion and domination. These pseudo-scientific distinctions, grounded in early anthropological and ethnological studies, sought to rank races and cultures hierarchically. By presenting physical differences as evidence of an inherent hierarchy, these theories provided colonizers with a framework to "analyze" local cultures while asserting their own supposed superiority. This constructed narrative portrayed non-Western cultures as inherently inferior, thus legitimizing European dominance over indigenous populations.

Architecture theorists notably contributed to these taxonomies, by proving the superiority of Western architecture, seen as more developed.

A prominent example of these theories is the 'Architecture Tree' by Banister Fletcher, who attempted to visually demonstrate the evolution of architecture style among different racial groups. According to Fletcher, the development of an architectural style is shaped by six key factors: geography, geology, climate, religion, history, and sociopolitical. At the top of his architectural tree, Fletcher placed Western European styles, which he traced back to Egyptian and Assyrian roots. Positioning Chinese, Indian, Mexican, and Peruvian architecture at the trunk of the tree, Fletcher suggested these styles are frozen in time and lacking a possible evolution. Theorists like Fletcher established hierarchies of style, and elevated Western architecture as the "superior" and "modern" model, while non-Western cultures were considered archaic and chronologically stagnant.

In 2016, anthropologist Johannes Fabian coined the term "denial of coevality" to describe the tendency to view non-Western cultures as existing in a different, often earlier, stage of development compared to the West. This perspective effectively denies these cultures their place in the shared historical present, reinforcing a narrative of Western superiority and progress.

In the 18th century, the prevailing belief was that climate and environment were key factors in a culture's success or failure. European Enlightners argued that exposing "underdeveloped" populations to a different environment or to external influences would help them modernize. This mindset equated “modernization” with “Westernization”. European cultures were viewed as the height of progress and civilization, leading to the assumption that other societies should adopt Western norms, values, and technologies to become modern.

For Viollet-le-Duc, the renowned French architect, known for the restoration of Cathédrale de Notre Dame, the evolution of an architectural style was predicated on the interaction between the Aryan race and other cultures. He argued that while the Aryan style could develop independently, the other races needed to engage with it to evolve from their archaic traditions.

« The man of the noble race (the Aryans) is born to fight in order to establish his power over the wretched races and to be the master of the earth. »

These racial theories did not disappear during the 20th century. Viollet-le-duc's theories spread globally and were found in the libraries of modern architects such as William Le Baron Jenney, Van Brunt, and John Root. Variations of the Aryan myth contributed to Western hegemony and to the belief that Westerners were destined to modernize architecture.

Owen Jones's ornamental theories characterizing non-Western ornaments as "archaic" or "primitive", were later echoed by Viennese architect Adolf Loos, who saw the elimination of ornamentation as a defining feature of global architectural modernity. This perspective extended to the use of Western construction materials like steel, glass, and concrete, which became synonymous with progress and modernity, further marginalizing traditional materials and techniques from non-Western cultures.

Repercussions: Western Education in Africa

Despite achieving political independence, the decolonization of universities and the built environment in Africa has progressed very slowly "to the point where buildings have become exotic in their own context". In many cases, students from newly independent countries expressed a significant reluctance to learn traditional architecture in their academic education, reflecting the persistence of Western cultural colonialism on a global scale.

A striking example is the Architecture faculty which opened in Ghana in 1957. Ironically, although Ghana became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to gain independence that same year, the architecture department was heavily shaped by the British educational model. Moreover, until the 1970s the architecture department was led by European directors, implementing a curriculum that prioritized international (i.e. Western) architectural theories and practices, with limited attention given to local building traditions. Even the students, largely from middle- and upper-class Ghanaian families, preferred this international approach over learning about indigenous architecture. This preference was driven by the belief that mastering the global (Western) architectural style would offer better career opportunities, reflecting the persistent perception of Western superiority in the field.

This reaction is not unique to students at the University of Ghana. In the ‘80s Nigeria, in the faculty of Architecture in Lagos, Professor David Aradeon tried to decolonize architecture pedagogy by encouraging his students to implement traditional forms and materials in their design for contemporary spaces. Aradeon faced tremendous challenges, not only from the academic establishment but also from the students themselves.

Initially, Aradeon had to confront Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, a British couple established in Nigeria, which was involved in the design and development of the university campus. The academic couple considered that:

« Local traditions in art and architecture has nothing which deserves the attention of a modern architect, nothing which deserves emulation. »

However, the student's initial resistance, which later escalated into strong opposition to integrating these local approaches, reveals less a genuine preference and more a result of indoctrination.

Need for renewal: an urgent for a more inclusive pedagogy

The 1960s and 1970s were marked by strong protests against institutions, where pedagogy was increasingly perceived as a political agent. In 1963, the writer James Baldwin gave a speech titled “Talk to Teachers", in which he addressed racial issues within educational institutions. Baldwin argued that schools had the power to generate significant societal transformations.

Protesters of the 1960s acted in several fields demanding greater representation and consideration of "non-whites, disadvantaged people, women, and people with disabilities and communities, among others". Writer and activist Bell Hooks speak of "white supremacist capitalist patriarchy" to convey to her reader that these systems are intertwined, feeding off each other and progressing simultaneously. It is therefore not surprising that the revolts of the 1960s jointly raised these themes for a simultaneous renewal.

Despite the student revolts of the 1970s, the active decolonization of architectural education has been a slow and ongoing process. As highlighted by the authors of Radical Pedagogies, which features the example of David Aradeon, these innovative experiments were rarely anchored in institutions and typically had a short longevity.

With this article, I hope to have shown that architectural education in universities is still deeply rooted in racial and imperial theories that define a conception of modernity belonging to the West. It is essential that when these theories are presented to architecture students, their colonial and imperial legacies are acknowledged. Moreover, universities must urgently expand their range of references by including non-Western architectural styles and promoting a vision of modernity that is specific to each culture and climate.

Recommended readings:

Radical Pedagogies (MIT Press, 2022): This book explores radical experiments in architectural education after World War II. These initiatives questioned modernist and colonial norms, redefining the role of the architect.

Purchase (with delivery in Switzerland):

https://www.copyrightbookshop.be/en/shop/radical-pedagogies/

https://www.abebooks.co.uk/9780262543385/Radical-Pedagogies-Colomina-Beatriz-Galan-0262543389/plp

Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present (Pittsburgh University Press, 2020): This book examines the influence of the often-ignored notion of race on architectural discourse and practice since the Age of Enlightenment. It explores how racial thinking shaped key concepts of modern architecture, such as freedom, national style, and progress.

Purchase (with delivery in Switzerland):

https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/Race-and-Modern-Architecture-by-Irene-Cheng-editor-Charles-L-Davis-editor-Mabel-Wilson-editor/9780822966593

Full PDF online:

https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/7935562/mod_resource/content/1/7_Carranza.pdf

Photos:

Charles White "An Account of the Regular Gradation in Man and in Different Animals and Vegetables; and from the Former to the Latter," 1799. Source: Public domain.

H. Strickland, "Ireland from One or Two Neglected Points of View", Drawing, 1899.

Fletcher, Banister. "Tree of Architecture" frontispiece of A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method for the Student Craftsman, and Amateur, sixteenth edition. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1954.

Bibliography:

Cheng, Irene, Charles L. I. I. Davis, and Mabel O. Wilson. 2020. Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh.

Colomina, Beatriz, Ignacio G. Galán, Evangelos Kotsioris, and Anna-Maria Meister. 2022. Radical Pedagogies. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

De Souza, Carol. Relationality in Place: Radical Pedagogy and Decolonial Space. Doctor of Philosophy at Monash University, July 2022.

Herrle, Peter. 2008. Architecture and Identity. Münster: LIT.

Patierno, Mary, Sut Jhally, and Harriet Hirshorn, eds. 1997. “Bell Hooks – Cultural Criticism & Transformation. Media Education Foundation Transcript.” Northampton, MA: Media Education Foundation. https://www.mediaed.org/transcripts/Bell-Hooks-Transcript.pdf

Piñón Escudero, E. 2020. “Coloniality and Museums: Architecture, Curatorship, Management, and the Perpetuation of Colonialist Structures.” http://hdl.handle.net/10251/139101

Shuchen Wang. 2021. “Museum Coloniality: Displaying Asian Art in the Whitened Context.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 27 (6): 720-737. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2020.1842382

Yalew, Emaelaf T. 2023. “Decolonizing Architecture in Africa: Rethinking Co-working Spaces in Nairobi”. Lund University, Mai 2023.

This article was translated with the help of AI.